Storytelling as a UX research method

- Emi Caulder

- Mar 10, 2023

- 3 min read

Updated: Mar 14, 2023

Storytelling has been incorporated into UX research techniques in diverse ways, and the routes taken can depend on a multitude of factors, from sample size to the product being tested. Iris Beneli is currently working on a year-long digital diary study where participants record videos of their thoughts that can later be played for executives in presentations, but she also often uses verbatim from surveys or interviews (Beneli). She says that “what really matters is if you find quotes that line up with the quantitative data and tell you 'the why' behind the issues you found” (Beneli). Gathering quantitative data is great and absolutely necessary for reporting results, but understanding the story behind the numbers makes the data digestible, meaningful, and relatable.

Dr. Turner meets with people at informal meals to make them comfortable and looks to gain an understanding of the “systemic nature” of the issues she finds (Turner). She also uses “artifact-based interviewing” (Turner), where the participant brings in an artifact that relates to the study and explains how it reflects their engagement with the experience. Getting this natural look at how a person interacts with the research topic and seeing what issues matter most to them can be valuable and may be missed in a regular research lab environment.

“I work from an asset-based approach, which means I believe that users and community members and organizations have existing skills, experiences, knowledges, and their own successful solutions to problems that many UX designers try to solve. Storytelling as a research and design method is critical to my process in a few ways—by informally meeting with users, communities, and stakeholders over meals, I am able to move beyond a traditional interview style and grasp the systemic nature of the problems at hand. I get to know people personally, gain trust, and structure opportunities for reciprocity that results in solutions that have long term impact” (Turner).

We can see naturalistic research like this in studies like Johnston’s (2022) project in preparation for a new academic building. Listening to students’ stories and perspectives from previous experiences with an existing library informed the design of an improved learning facility. With observation of real students in the space and open-ended interview and survey questions, the study could capture students’ stories and “enable libraries to use evidence-based results along with internal expertise” (594) and anecdotal evidence. Understanding how someone really lives their life and listening to their wants and needs can make all the difference.

I also asked Iris Beneli about her use of personas in UX research, and she said she no longer uses them much. They are often not “married in data” (Beneli). When she worked at Kohl’s, her team did a cluster analysis of a survey to make composite personas. Laughing, Beneli recalled, “One of our personas was an artist. I found a stock photo and everything, and then my colleague wrote him as color blind” (Beneli). Now she doesn't really do personas or focus groups, either: “Too much noise, too much opinion. You need behavioral data” (Beneli).

She doesn't think it's necessary to make up a fake persona when there are already real people to study—like the participants in the Empathy Program at her current position at Google Workspace, which aims to see whether business users actually want the systems her team is spending a ton of time producing. So it can be tricky to compile and organize peoples’ stories and find a balance between hard facts and emotional experience. Iris recommends finding the facts and seeing if the direct quotes align.

Nora Rivera, an expert in rhetoric and composition who studies the connection between culture and technology, spoke with indigenous interpreters and translators in technical communication and mapped testimonios as a UX narrative method (Rivera, Nora). She looked at how UX researchers may “engage with testimonios as an indigenous method that promotes agency and supports user advocacy” (Rivera, Nora 9). Testimonios share narratives of lived personal accounts which often connect to shared collective experiences (Rivera, Nora 12), just as UX studies with relatively small sample sizes may be generalized to the broader user group. The telling of testimonios not only therapeutically shares indigenous emotional turmoil, but also can be used as a qualitative UX research method, as this study did when exploring issues indigenous interpreters and translators face in Western systems, participants’ personal and collective issues in the context of their communities, and participants’ civic engagement (Rivera, Nora). Using this information from testimonios, UX researchers can create better research experiences for indigenous individuals and individuals who are part of other underrepresented groups, localizing “the design of content, products, and processes in a way that better aligns with the different contexts and experiences of indigenous groups and other diverse groups” (24). Taking the time to listen to personal experiences throughout the research process creates a more inclusive, informative study.

(Ray) (Zaidi)

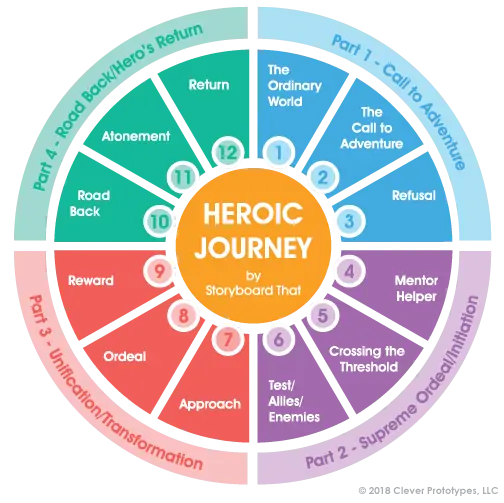

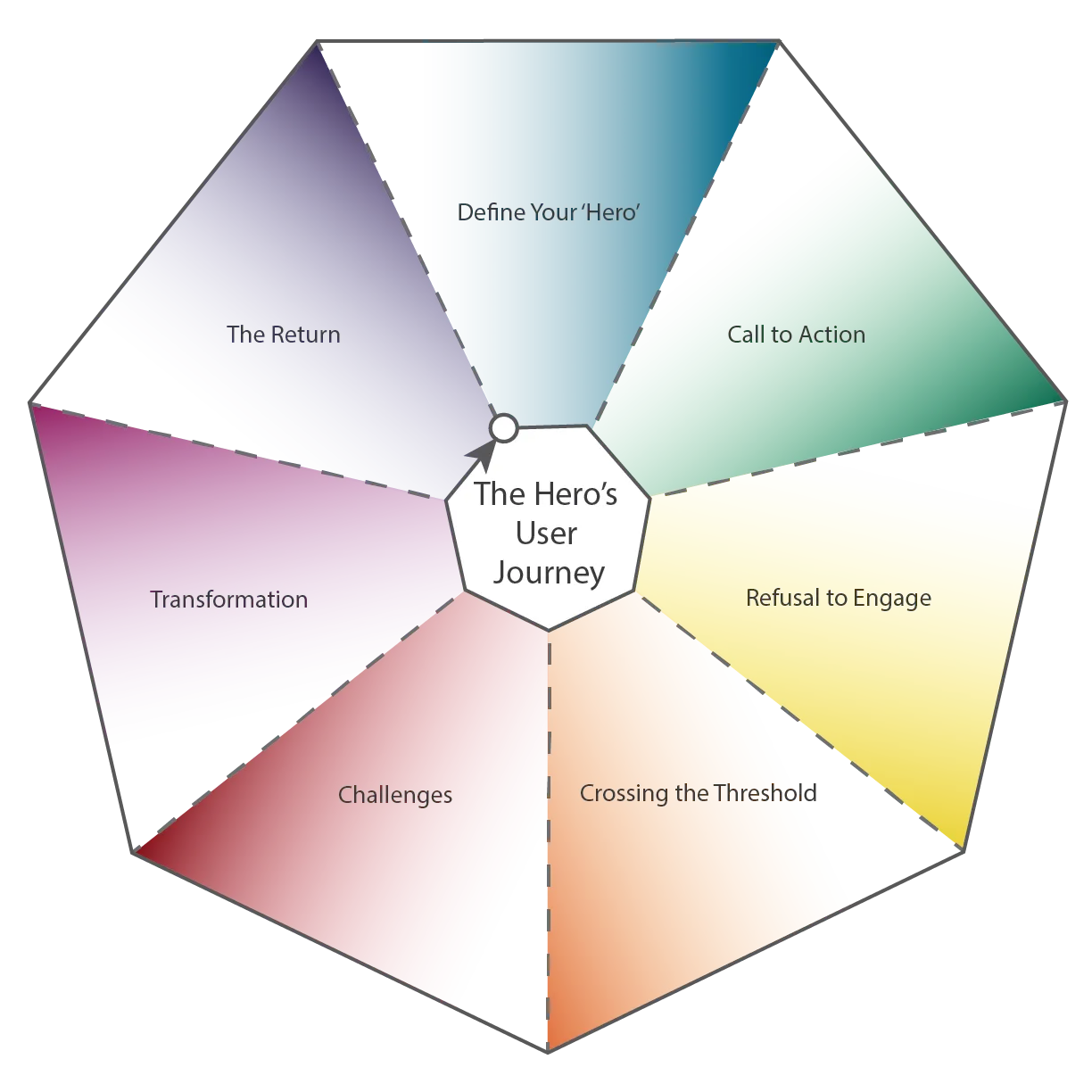

The user's journey through a product experience has been compared to the hero's journey in classic narrative.

Comments